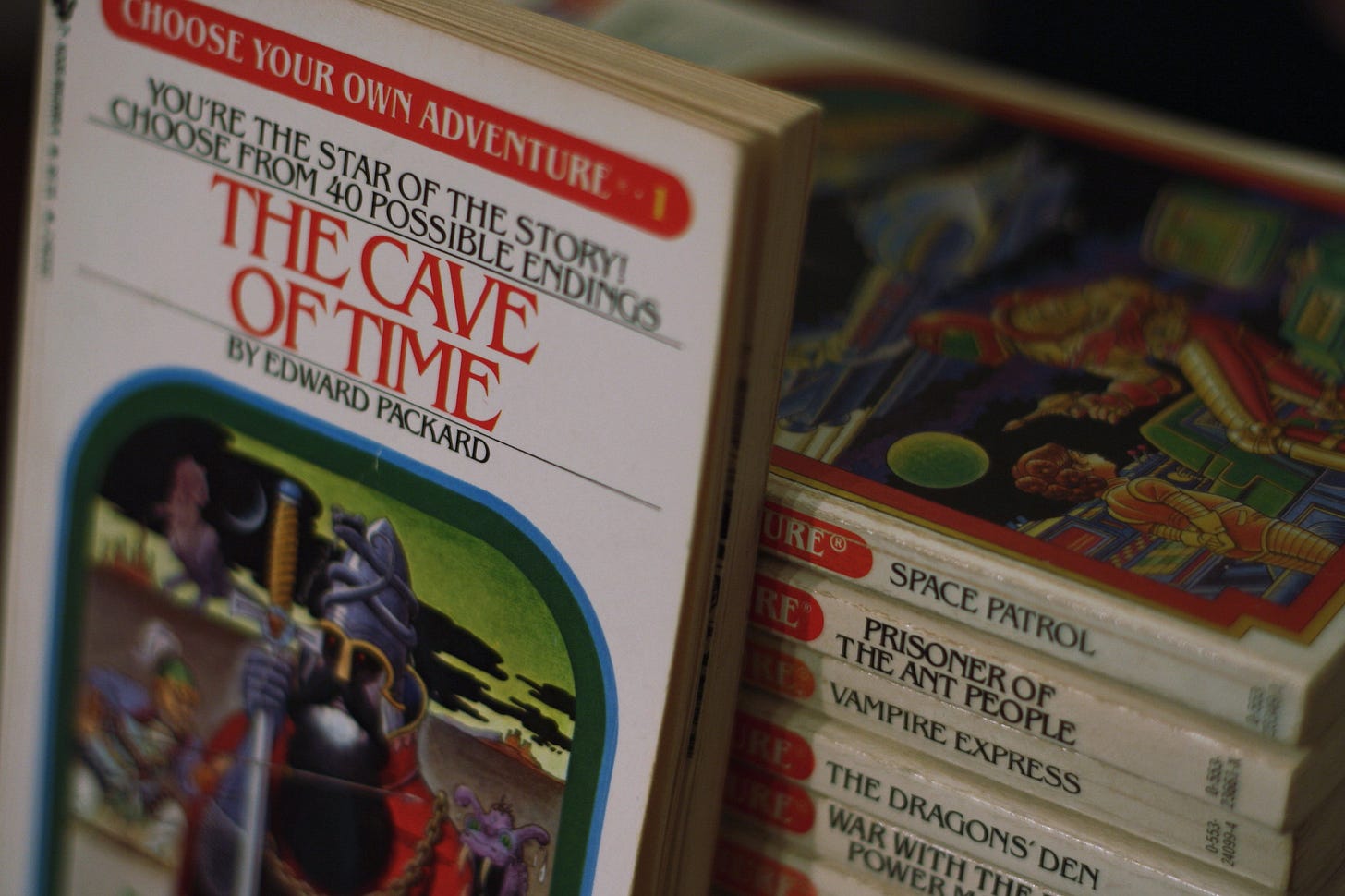

Ode to the Scholastic Book Fair!

Growing up I loved Choose Your Own Adventure books. The idea that I could influence the story was fun and exciting. I would read, choose a page, not really like where it took me, return to the last page or start over, and choose again, and again, and again, trying to find the perfect ending to the story. I don’t remember ever being truly satisfied with these books, but I was obsessed and filled with hope, and every year a new cover would catch my eye and I’d get my mom to buy me one.

This feeling of having choices, but not quite being able to choose the right page or find a satisfying outcome returned when I began managing my daughter’s healthcare journey.

It looked something like this:

On page 4 Daughter finally receives a couple of weird but real diagnoses after years of hearing some version of “it’s all in your head.” We are given an eight page print out of information and suggestions designed by the doctor, complete with clip art, as well as a set of protocols to follow. If she does all of this it will probably help her manage her symptoms, and to check back in 3-6 months.

Where do we go next? The choices are:

Page 67: Overshare to friends, family and a few random strangers. No one in your circle has heard about these weird illnesses and are a little suspicious of the plan of care. You realize you’re just trying to make sense of this new plot twist and are looking for solidarity. Instead you hear suggestions like, “has she tried yoga?” and to “set better boundaries.” Both perfectly good suggestions, you’re just not there yet. You’re overwhelmed and dealing with her school, teachers, and extra curricular activities and feel like you’re going in circles waiting for the follow up appointment but it’s been good to talk about it.

Page 25: Hold here and follow the protocols as prescribed:

If this resolves the symptoms, go to the last page which reads Congratulations! (You only know this because you peeked).

If no meaningful change is experienced, go to page 84 where you’re told at the next follow up appointment that these treatments take time to work, so you watch her continue to suffer and remind her every hour or so to mind her protocols (it’s super cool to nudge your teen like this and she loves it—she does not love it). There does seem slight improvements here and there, just enough to keep nudging.

Page 31: She follows the protocols as prescribed, but the symptoms seem to be getting worse or cycling through levels of severity that have patterns. So you keep digging and asking questions to find more answers (and honestly more questions). The leading answer is to keep following protocols. You ask a lot of questions about co-morbidities and physical anomalies and responses tend to be: “that’s too rare”, “it’s doubtful she has that”, and a variety of others in this vein.

(If you skip ahead to page 81 you would see that she does in fact have a few of these, but you’ll need a couple of more years and at least 10 more doctors for that to be realized.)Page 43: You find a community. Even though you are warned not to listen to people online, you realize that there are groups of people that have been there and understand what you’re going through and this make you feel less alone. This could help you learn more about the illnesses, ask better questions, and find more support, but it’s also overwhelming and you’re not sure you can handle one more thing right now.

Choice in Complex Chronic Illness Care

I often say that managing chronic illness feels like a Choose Your Own Adventure book, but it’s been hard to put into words exactly why I feel that way. While the books often left me feeling less than satisfied, there were also moments of joy, exploration, and fun as the game unfolded. And maybe approaching the last few years with this perspective helped me manage the roller coaster ride of chronic illness care.

Generally, in healthcare, I feel we are sold the idea of choice but we never really talk about the constraints (pages) that frame what we’re given to choose from or that the system (book) has been designed in a way to lead us down a limited number of (story) resolutions.

The fun part of Choose Your Own Adventure books is that they are not meant to be read like a book. If you try to read them cover to cover the stories will not make sense. Of course you can cheat and look ahead to try to make informed decisions, but the game is in trying a path and if you don’t like it, having more options to choose from. This gives some agency to the reader and allows the story to branch off in different directions.

Chronic illness care also creates these branches that may not fit into typical healthcare models. If the model is getting sick, going to the doctor, having tests run, given a diagnosis, receiving something to mend or fix the issue, and maybe one or two follow ups to settle the case, then chronic illness disrupts this by repeating the process multiple times and branching off at different steps along the way.

While there is some agency to choose, it is limited by the constraints and expectations of the system (healthcare, education, interpersonal, etc), those we meet within the system, and where our various systems overlap. There is so much I want to say about this. For starters many of those with chronic illnesses deal with a lack of choice simply because there is a lack of social awareness about their illness, a lack of desire to increase and apply research funding, and a lack of access to resources that are often framed by able-bodied perspectives. I would love to expand on these, but today I’m interested in highlighting the branching off that leads to a trial and error approach in the chronic illnesses model.

Leaning into the Scientific Method

With some chronic illnesses, especially invisible and complex cases, there is a high level of uncertainty which leads to a lot more active hypothesis making, testing, and data collection to help make informed decisions. This is done in real time with the patient. For example one of the non-pharmacological protocols for POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome) is to increase salts and fluids. There is a general guide line for best practices, but what works best for each body is a trial and error of learning to balance activity levels, environmental and weather changes, possible GI issues, and a host of other variables, with the daily amount of salt and fluids required to manage symptoms.

This trial and error approach can be tough and frustrating. Following a scientific method is slow and it doesn’t always lead to a favorable outcome. There are a lot of protocols and trials that might need ongoing tweaking or not work at all. That is the nature of its design. It’s not looking for universal truths, its looking to offer data points towards a specific question. The more questions explored, the more data points collected, the more opportunities there are to create a synthesis of understanding and improve the outcome.

This is the frustration and the complexity. The interconnection of multiple data points on any given day to support illness symptoms. Key here is that most of time we are not even looking for a cure, but an improvement to quality of life. And quality of life is impacted by the choices available. Which makes quality of life political, debatable, and filled with judgement often handed down by people outside of the doctor’s office. When someone with a chronic illness goes into a doctors appointment all of this comes with them and we haven’t even touched on the choices constrained by insurance, location, and access to these appointments.

When the whole person beyond the illness is taken into consideration and when more individual trial and error experiences are documented, then more choices can be advocated for by patients and their caregivers. Each of these choices, big and small, make up the whole story. And it’s story that is still being written.

So, What Page Did You Choose?

Looking back I can tell you that we made all the choices listed above at one point or another. Just like the Choose Your Own Adventure books if we got to a page we didn’t like we circled back and tried again. There was a lot of frustration and suffering with this path, but there was a lot of learning too.

Essentially we understood that we were navigating systems that are set up to triage emergencies and treat better known illness but that hasn’t quite found a way to fit the management of chronic illnesses into that same model. In reality, we needed a different set of choices, and maybe even a different book.

Making (Unpopular) Choices

I was the first mom I knew dealing with these issues and the uncertainty of everything was overwhelming. For a while I didn’t even know what we were dealing with. There was so much I was getting wrong and I felt like I wasn’t asking the right questions because none of the answers made sense to us.

Going online to find a community was scary because there was an overwhelming amount of information. I was worried that a lot of people going online looking for answers had severe cases and it was terrifying to think of my daughter’s case as severe. But, it was also a place I found a great deal of comfort, there was a lot of solidarity and a lot of moms who had been through the trials and errors and understood how crazy it all felt and were now giving back.

I found answers I couldn’t find anywhere else and suggestions we could bring to her doctors. These support groups were reframing outdated or unhelpful information which helped me change the way I approached my daughter’s care. And I began to see trial and error as a necessary part of the experience, which is to say that being curious and using my imagination to think critically and creatively was one of the most important things I could have done. And this is where the Choose Your Own Adventure books come back in.

We began to understand there were going to be choices, and that sometimes these choices were going to be framed in impossible ways. But no matter what path we went down we could always circle back and try again. We never had to close the book, we could keep trying. I think if I could have thought about it this way in the very beginning it may have saved me a lot of headaches. When we started the journey we didn’t have a playbook, we didn’t even a page one. But, we were learning how to make the next best choice, which gave us more agency and hope than we felt in the moment and allowed the branching off to be places to gather information and be informed participants.

Access to knowledge, research, and the lived experience of others improved our decision making and helped us ask for better choices. While we still feel the constraints of a system not fully prepared to manage chronic illness, we do feel like we are partners supporting a bigger solution and we are finding ways to give back too.

With care,

Tami

Side note: There are hundreds of Choose Your Own Adventure books! but I haven’t seen any medical ones… yet! What do you think one would look like?